Sweden

Sweden's circularity indicator framework

To accelerate the transition toward a circular economy, we need to use data and data-driven insights in the best way to support top-level decision making. At the same time, given the breadth and scope of a systems change towards a more circular economy, local and bottom-up grassroots initiatives are equally crucial to drive changes forward at the community level. To address the complexities and intricacies of a nation’s economy, we aim to provide as much information and context on how individual nations can better manage materials to close their Circularity Gap. In our Circularity Metric Indicator Set, we consider 100% of inputs into the economy: circular inputs, non-circular flows and non-renewable inputs and inputs that add to stocks. This allows us to further refine our approach to closing the Circularity Gap in a particular context and answer more detailed and interesting questions: how dependent are we on imports to satisfy our basic societal needs? How much material is being added to stock like buildings and roads every year? How much biomass are we extracting domestically, and is it sustainable? These categories are based on the work of Haas et al. (2020). [24]

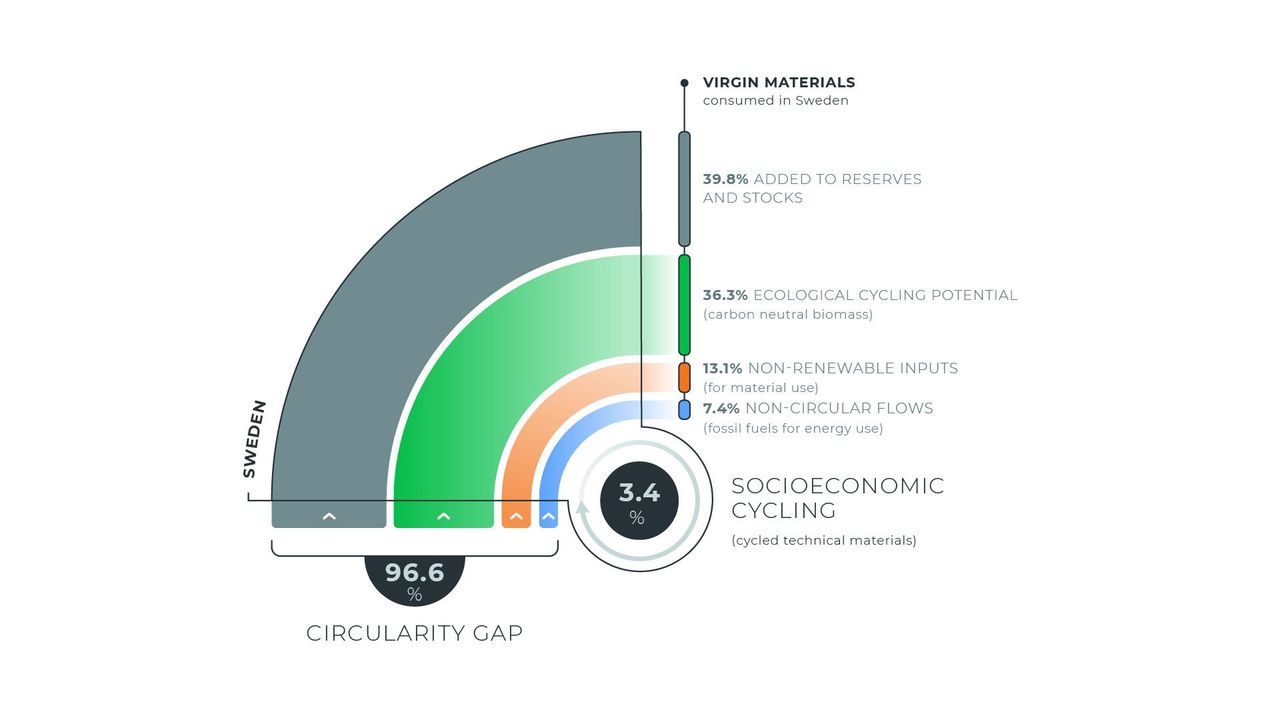

Figure two shows the full picture of circular and non-circular materials that make up Sweden's Circularity Gap.

Circular inputs

These are the materials flowing into an economic system that contribute to a circular economy. This means they're used in a way that prioritises reuse, recycling, and regeneration over virgin extraction and waste disposal. This category includes two indicators: the Socioeconomic Cycling Rate (or 'Technical Cycling rate' or 'Circularity Metric') and the Ecological Cycling Potential Rate.

1. Socioeconomic Cycling Rate (Circularity Metric)

This refers to the share of secondary materials in the total consumption of an economy: this is the Circularity Metric. These materials are items that were formerly waste, but now are cycled back into use, including recycled materials from both the technical (such recycled cement and metals) and biological cycles (such as paper and wood). In Sweden, this number is well below the global average of 8.6%, totalling 3.4% of total material input.

These are inputs that should be aimed to be maximised as much as possible.

2. Ecological Cycling Potential Rate

Ecological cycling concerns biomass, such as manure, food crops or agricultural residues. To be considered ecologically cycled, biomass should be wholly sustainable and circular: this means it must, at the very least, guarantee full nutrient cycling (read more in the text box on the following page)—allowing the ecosystem biocapacity to remain the same—and be carbon neutral. Because detailed data on the sustainability of primary biomass is not available, the estimation of the ecological cycling potential needs to rely on a broader approach: if the amount of elemental carbon from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) emissions is at least the same as the carbon content of primary biomass in the total consumption of an economy, then all the consumed biomass can be considered carbon neutral. The huge volume of forested area in Sweden that is economically and socially sustainably-managed provides a significant basin for carbon sequestration, meaning that Swedish LULUCF emissions are certainly negative, and the biomass consumed within its borders can be considered carbon neutral.

These are inputs that should be aimed to be maximised as much as possible.

Why don't we include ecological cycling potential in the circularity metric?

While carbon neutrality is a necessary condition for biomass to be considered sustainable—it is not the only condition: nutrients (including both mineral and organic fertilisers) must be fully circular as well. Nutrient cycling is like biological recycling: it is the process by which matter decomposes and is transformed into new matter at the end of its lifetime. As of yet, we have methodological limitations in determining nutrient cycling: for example, we cannot track where Swedish timber products end up around the world, or how they are managed at end-of-life. To this end, we have not included ecological cycling in our calculation of Sweden's Circularity Metric—even though this could potentially boost the country's circularity rate to an impressive 39.7%. We take a precautionary stance with its exclusion, with the knowledge that its impact on the Metric may not be totally accurate—we cannot track biomass extracted in Sweden to its final end-of-life stage, so it's difficult to ensure that the nutrient cycle has closed. If this were the case, however—and the sustainable management of biomass becomes the norm—circularity could greatly increase.

Linear inputs

Linear inputs make up the Circularity Gap: they’re materials that follow a take-make-dispose model and aren’t cycled back into either technical or ecological systems. This category comprises two indicators: the Non-Renewable Rate (materials that could be recycled but currently are not), and the Non-Circular Rate (fossil fuels used for energy) and the Non-Renewable Biomass Inputs.

1. Non-Renewable Rate

Non-renewable inputs into the economy—that are neither fossil fuels nor non-cyclable ecological materials—include materials that we use to satisfy our lifestyles such as the metals, plastics and glass embodied in consumer products. These are materials that potentially can be cycled, but are not. Sweden's non-renewable input rate stands at 13%, suggesting that there is room for the improved cycling of non-renewable materials.

These inputs should be cycled into secondary inputs as much as possible.

2. Non-Circular Rate

This category centres on fossil fuels for energy use. Fossil-based energy carriers, such as gasoline, diesel and natural gas that are burned for energy purposes and emitted into the atmosphere as greenhouse gases, are inherently non-circular. They combust and disperse as emissions in our atmosphere: circular economy strategies are not applicable here, as the loop cannot be closed on fossil fuels. At 7.4%, Sweden's rate of non-cyclable inputs is relatively low. This is in line with the low-carbon character of the Swedish economy. While the majority of electricity and heat comes from renewable sources, Sweden is still dependent on fossil fuels for other processes such as industrial energy use and transport.

These inputs should be minimised as much as possible.

3. Non-Renewable Biomass Inputs

Non-Renewable Biomass Inputs represent the share of primary biomass—such as trees, manure, food crops, or agricultural residues—that is not considered carbon-neutral, measured as a proportion of total material consumption.

These inputs should be minimised as much as possible.

Net additions to stock

The vast majority of materials that are ‘added’ to the reserves of an economy are ‘Net additions to stock’. Countries are continually investing in new buildings and infrastructure, such as to provide Mobility and Housing, as well for renewable energy, such as building wind turbines. This stock build-up is not inherently bad; many countries need to invest to ensure that the local populations have access to basic services, as well as buildup infrastructure globally to support renewable energy generation, distribution and storage capacity. These resources do, however, remain locked away and not available for cycling while in use, and therefore weigh down the Circularity Metric.

These inputs should be reused and cycled where possible to extend material lifetimes or reused as secondary materials.

If continued stock build up is inevitable - should it be considered part of the 'Gap'?

Stock build up will continue to be necessary as Sweden’s population grows. However, Sweden's rate of stock build-up is also relatively large due to a range of interlinked social, cultural and geographic factors. An appetite for attractive architecture and preference for living alone are characteristic of the country: Sweden has the highest rate of single-occupant houses in the EU, with over half of the households containing just one person.26 Its spread-out geography and low population density in rural areas also necessitate infrastructure build-up—for roads and energy provision, for example—to accommodate residents. But the country's high stocking rate may not be inherently problematic, especially if circularity is afforded attention in the design, use and end-of-life phases. For this reason, some may argue that Net additions to stocks should not be considered part of the Circularity Gap. If all the materials locked into stock were not considered as part of the full indicator set, the Circularity Metric would increase substantially. So why don't we do this?

The Circularity Metric is ultimately a measure of what is cycled—not just what is circular—and materials added to stock can't be cycled for many years, potentially decades, if not more. What's more, the circularity of materials added to stock cannot be ensured: it is not always clear which portion of these materials are designed and used with cycling in mind or to what extent they are regenerative and non-toxic, for example. The bottom line is that the built environment consumes a huge volume of resources: its impact on Sweden's overall consumption should not be ignored, especially given crucial resource depletion concerns.

The Circularity Gap Report is an initiative of Circle Economy, an impact organisation dedicated to accelerating the transition to the circular economy.

© 2008 - Present | RSIN 850278983